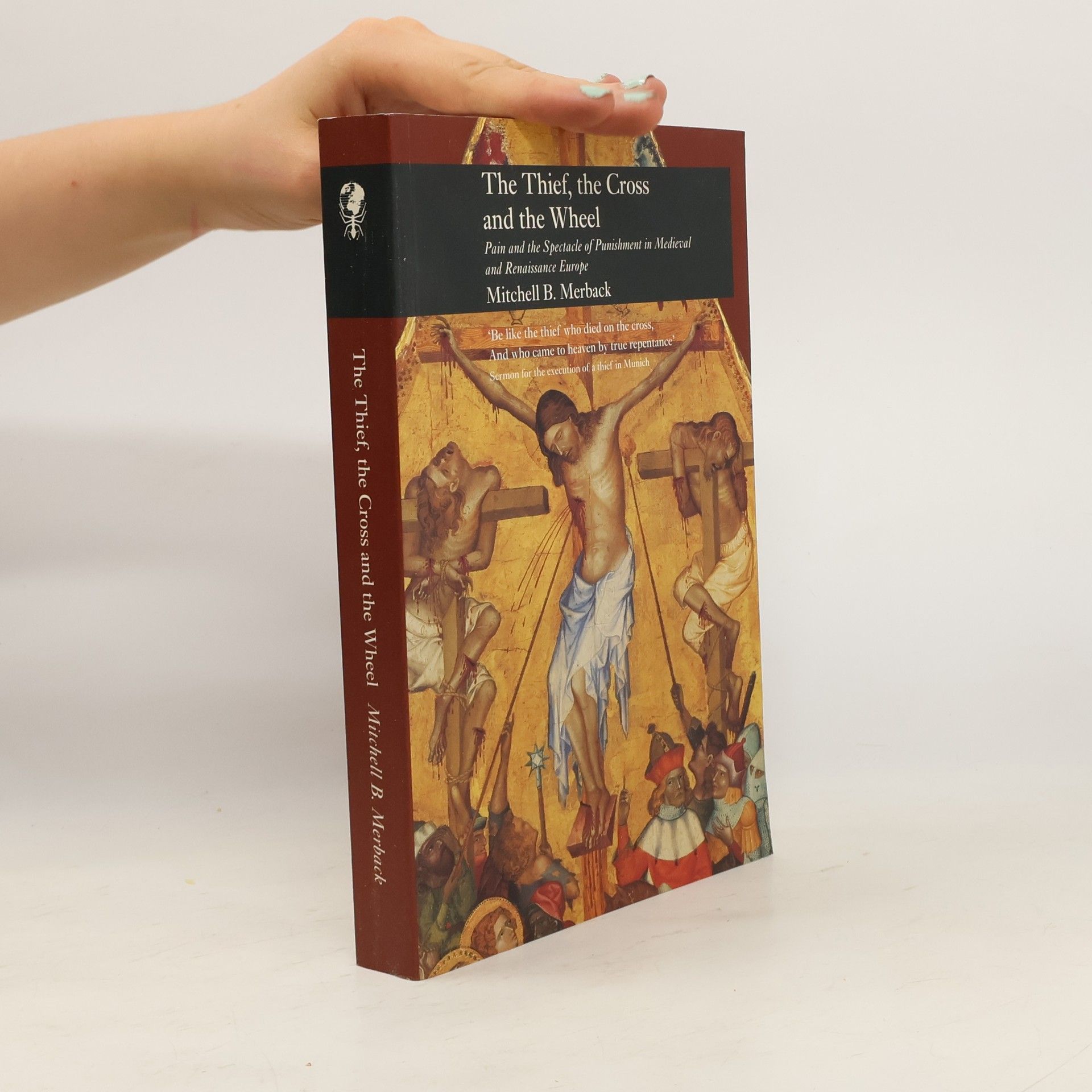

The Thief, the Cross and the Wheel

Pain and the Spectacle of Punishment in Medieval and Renaissance Europe

- 325pages

- 12 heures de lecture

When spectators in the Middle Ages examined images of Christ's crucifixion on Mount Calvary, did they ever consider them as representations of capital punishment? This book traces out the extraordinary connections between religious devotion, bodily pain, criminal justice and judicial spectatorship to explain why this was so.